Wednesday, November 20, 2019

Lessons Learned: ONRSR & GWA - Whyalla Runaway Incident

This document shares findings made from a runaway incident that occurred on 31 July 2019 in Whyalla, South Australia that should be used as an input to the risk review processes for operators managing a similar operating scenario.

This document has been written to share with industry findings made from a runaway incident that occurred on 31 July 2019 in Whyalla, South Australia that should be used as an input to the risk review processes of all operators who may manage a similar operating scenario.

Genesee & Wyoming (Aust) Pty Ltd (GWA) endorse the distribution of this document and are to be congratulated for being open and transparent by sharing learnings from this incident.

What happened?

On Wednesday 31 July 2019 Train No. 41 (consisting of CK4 & GWN005 locomotives and 28 2-pack ore hoppers, total length of 626 metres and 1420 tonnes weight) rolled backwards uncontrolled on the narrow-gauge railway network within the GFG Liberty Primary Steelworks at Whyalla, in South Australia. The train proceeded through the steelworks, reaching a (recorded) speed of 50km/h, stopping on the Inner Harbour Tip Pocket balloon loop, where it was secured against further movement. The train travelled approximately 6 kilometres and passed through 1 passive pedestrian and 7 actively protected road crossings.

The train had stopped of its own accord due to near flat track grades around the balloon loop, no casualties or infrastructure damage were recorded.

The incident occurred during transition from remote control to manual control, while a driver was preparing the train for travel.

What did ONRSR and GWA find during their investigations?

Safety issues identified include:

- The need to allow time for the train brake pipe to discharge between turning off the operator remote-control unit and isolating remote-control air control valves in the locomotive was not identified within the procedures. This led to a situation where the air in the train brake pipe was not vented enough to trigger a brake application on the train, effectively “bottling the air” in the train brake pipe.

- Reliance on independent brake to hold locomotives and empty ore wagons on a gradient while operations are being undertaken.

- Air Brake control handles were not stored in a standard location in the locomotive cabs when removed from the brake stand by drivers, leading to the situation where the driver could not locate them.

- No use of secondary protective devices (i.e. derailers, catch points) by the network owner at locations on the interworks or mine railway networks where it was necessary to contain a runaway train to prevent an escalation of risk associated with collisions between vehicles or other rolling stock.

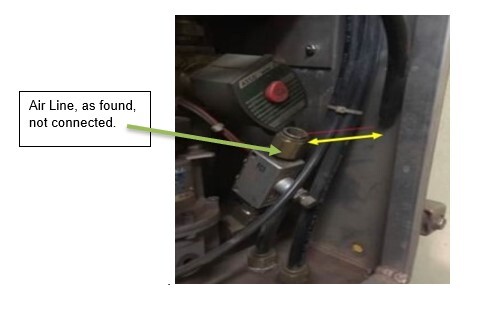

GWA through their own investigation identified an air leak on No 3 pipe in the brake system. A hose within the Pneumatic Control Unit (PCU) that was not sitting in a connector allowed the locomotive independent brakes to bleed off and release. A flow monitor associated with this hose was also set in a restrictive state.

It is unclear how this pipe became loose.

The PCU uses proprietary push-fit (also known as push-to-connect or “Fastlok”) pneumatics connectors. The connector associated with the loose pipe was a brass fitting, not a plastic one. These are commonly used in pneumatics installations and are rated to pressures of up to 215psi/1500kPa.

Therefore, the possibility that the pipe was not reinstated into the connector cannot be confirmed or eliminated and therefore remains a potential source of failure.

The investigation did confirm that the pipe was not connected to the circuit (after the incident) and that this irregularity allowed the independent brake to bleed off. This is considered a contributing factor to this incident.

Lessons Learned

ONRSR encourages rolling stock operators to consider the points outlined below. Please note that these are not to be deemed as issues identified during the investigation of this particular incident but considerations that all operators of similar type remote-control rolling stock should deliberate.

1. Risk management

Generic risk assessments relating to train operations may not adequately incorporate the specific hazards relating to remote control operation. To ensure understanding of risks surrounding remote control operation these should be considered and clearly documented independently.

While this runaway was not directly attributable to remote control operations, the failure of remote-control systems and their potential to result in a runaway should be examined and risk assessed in context of the location where remote-control operation and its interface with conventional operations is performed. Locations of remote-control operations must be considered due to variations in topography, speed restrictions, track condition and controls such as catch points that may impact the risk consequence.

The risk process must consider other train systems that interface with the remote-control system and contribute to the risk such as train braking systems. The remote-control safety systems (fail safe) rely on the locomotive and train braking system to be operational, and as a result the risk assessment should consider failure of multiple systems.

Risk assessment teams assessing risks relating to remote-control operations should include the Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM), rail safety workers who operate remote-controlled systems, rail safety workers who maintain the remote-control systems, trainers, network controllers and any other relevant parties to ensure a high level of technical expertise and experience.

Risk assessments relating to the integrity and security of communication systems of the remote-control system should be considered and documented.

Incidents experienced by other operators and relating to remote-control operation should prompt a review of an organisation’s risk register to reasonably ensure any resulting lessons learned have been considered.

2. Maintenance

Technical and maintenance information relating to remote-control systems should be comprehensive, complete and encompass all parts and components of the system including electrical and pneumatic interface drawings.

Technical data should be current and relate to the actual remote-control system in use and not a generic maintenance manual that may include information that is not applicable.

Systems and procedures associated with maintenance, inspection and testing of remote-control systems should be consistent with OEM standards and recommendations and documented in the organisation’s safety management system.

An approval process is required to verify remote-control systems or components that have returned from maintenance are fit and safe to reintroduce into service.

Detailed maintenance records relating to remote-control systems should be retained and examined for trends.

It is important the organisation understands the remote-control system software including updates and versions. Records of software intervention must be maintained with identifying information physically marked on the equipment.

The skills and competency necessary for maintenance personnel to carry out repairs, inspections and testing of remote-control systems should be determined in consultation with the OEM and documented in the organisation’s safety management system.

To ensure a holistic approach, maintenance personnel who carry out repairs, inspections and testing of remote-control systems should be trained and hold competency to carry out such work including electrical and pneumatic qualifications. Understanding how the remote-control system interfaces with the locomotive systems should form part of this competency.

To reduce the risk of incorrect fitment of air hoses for the remote-control system interface, a standardised colour code system should be utilised.

3. Remote Control Operators

Material used for training rail safety workers who operate remote control systems should be current and relate to the actual remote-control system in use.

Training rail safety workers who operate remote-control systems should include understanding of other train systems such as the air brake system and how it interfaces with the remote-control system.

Training material for rail safety workers who operate remote-control systems should consider combinations of emergency events such as remote-control safety systems failure and train air brake failure.

Competency evaluation of rail safety workers who operate remote-control systems should be frequent, reoccurring and documented.